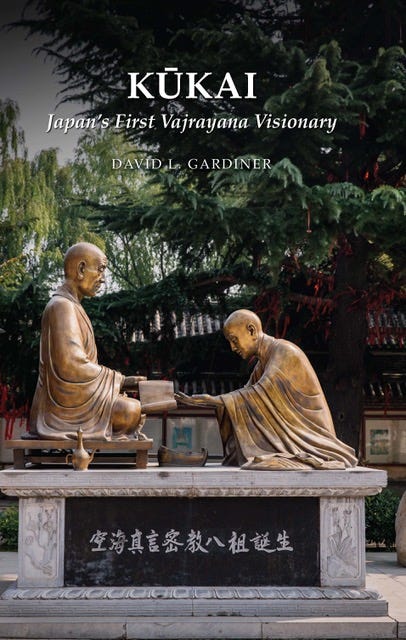

Kūkai: Japan's First Vajrayana Visionary

new publication in the Contemporary Issues in Buddhist Studies Series

Kūkai (774–835) is a key figure in the history of Buddhism in Japan, despite the greater attention frequently paid to later figures associated with Zen, Pure Land and Nichiren traditions. The teachings and practices of the form of Buddhism that he introduced, the Shingon lineage (“true word” vehicle, that is, mantrayāna), influenced all of the other Buddhist traditions as well as the various strains of medieval Shintō and Shugendō (more commonly, Yamabushi) from that time on. For the study of Buddhism, his work takes place in the intersection of East Asian and tantric Buddhism. The first new book length treatment of Kūkai in English in over a decade, David Gardiner provides important perspectives on Kūkai as a creative religious thinker of the first order.

This volume in the Contemporary Issues in Buddhist Studies Series is published by the Institute of Buddhist Studies and BDK/America. The Series is marketed and distributed by the University of Hawai‘i Press <link>–look for it there later this summer.

Series Editor’s Preface

The history of Buddhism can be written as a dialogue between dualistic and nondualistic conceptions of the path. These two alternatives ramify through every aspect of Buddhist thought and practice. A well-known instance is the question of whether awakening is accomplished through a gradual process, or is a sudden event—is it a path one progresses along until finally reaching a point from which the goal is inevitable, or is it a leap across to a different way of seeing, of being, of engaging the world? Equally, the understanding of the two truths evidences this dialogue. Are the two truths those of an exalted absolute and a merely relative? Or are they one truth expressed simultaneously as emptiness and as conditioned existence?

This kind of distinction also structures how thought and practice are understood to be related to one another. Are doctrines foundational and practice an expression of those ideas? Is practice foundational and doctrine an attempt to express how practice works? Or are the two dialectically related with one another, each influencing the other?

As laid out for us by David L. Gardiner, Kūkai’s vision falls resoundingly on the nondual side of this dialogue. And in a further twist, it provides a basis from which to understand the dialogue itself as a nondual interaction. Kūkai’s formulation shares much with other nondual and tantric strains within the history of Buddhism, including his emphasis on taking the goal—embodying buddhahood—as the path.

Gardiner opens this work on Kūkai’s transmission of esoteric Buddhism to Japan by noting the importance of his integration of tantric thought and practice into a coherent system. The Shingon tradition considers that thought and practice are not autonomous or separate, but rather dialectially integral. This is key to understanding Kūkai and his influence on the entire history of religion in Japan from the Heian era to the present. The integral relation between thought and practice Gardiner highlights also points to a key theoretical issue for the study of Buddhism more generally, and indeed for religious studies as a whole. Both disciplines perpetuate the idea that thought and practice are distinct, and that thought is determinative of practice.

In addition to these theoretical concerns, Gardiner raises an issue of terminology. For the most part, scholarly discourse regarding Shingon and other forms of Esoteric Buddhism in East Asia has avoided the term “Vajrayana.” It has been almost exclusively used in relation to Indo-Tibetan forms, particularly later tantric texts from India that emphasize the symbolic significance of the vajra. Gardiner, however, uses it throughout this work to identify the kind of Buddhism practiced and propagated by Kūkai. In personal correspondence with the author, Gardiner has pointed out that Kūkai himself employs ”Vajrayana,” and more frequently, vajra treasury (or piṭika) 金剛藏, to describe the teaching and practice of his lineage.

Asserting that Vajrayana is an appropriate name for the Shingon tradition is important because it serves to subvert the privileging of Indo-Tibetan tantric traditions. That current scholarship privileges the India–Tibet axis would seem to reflect internal Tibetan discourses and disputes regarding authority, which is located in the Sanskritic Buddhism of India. In doing so, the wide expanse of the tantric tradition throughout Buddhist history is marginalized and obscured.

What unifies so much of the tantric movement across the entirety of the Buddhist cosmopolis is the threefold practice of mudrā, mantra, and mandala, integral to the conception of practice as one in which the path and its fruit are identical. The always and already awakened state is made manifest for the practitioner in the ritual act of identification—the three secrets in which the body, speech, and mind of the practitioner and the buddha are experienced as a unitary identity. As Gardiner and others have demonstrated, Kūkai’s practice is firmly based on engaging these “three secrets.”

Kūkai’s contributions to the history of Buddhism have at times been reduced to institutional history. Equally reductive, his teachings have been treated as philosophy, as sectarian doctrine, or as discursive. Such reductive treatments miss, or actively evade, considering Kūkai’s efforts as an integral whole. In Kūkai: Japan’s First Vajrayana Visionary, Gardiner emphasizes a more unified approach. He argues for a shift of focus from Kūkai’s engagement with doctrine to his exhortations toward practice, and emphasizes Kūkai’s vision of practice in the broader scope of his exhaustive efforts to establish initiation rituals, new institutions, conversations across perceived boundaries, and writing doctrinally formative texts.